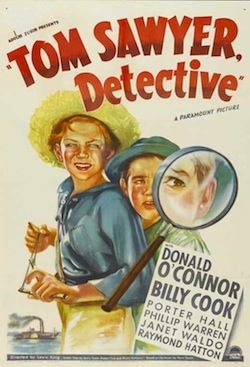

Tom Sawyer Detective, Mark Twain’s 1896 contribution to the incredibly popular detective genre, was published just two years after his spoof of the adventure story, Tom Sawyer Abroad. Just as he was able to use Tom and Huck to play with conversations full of false logic and elements of travel writing in that book, Twain continues to reveal that his two star characters are incredibly versatile and can fit into the conventions of a number of different genres.They can mimic the pirates, robbers, and adventurers that Tom reads about in books. In this novel Twain homages the work of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who had been popularizing both the revelatory mystery format and the almost supernaturally observant detective for half a decade prior to the publication of Tom Sawyer Detective.

Brace Dunlap, a powerful and surly neighbor of Tom’s Uncle Silas (from whom Tom and Huck tried to steal the already freed Jim in Huckleberry Finn), is terrorizing the poor old man because his daughter has refused Brace’s marriage proposal. Chief among Brace’s revenge tactics is pressuring Silas to pay Jubiter Dunlap, Brace’s good for nothing brother, to help him on his tobacco farm. When it becomes clear that Jubiter’s lackadaisical approach to farm work will drive the usually peaceful Silas mad with rage (he’s even begun sleepwalk), Aunt Sally summons Tom and Huck back to Arkansas to provide some distraction for the entire Phillips family. Eager for the opportunity to cause trouble on the road, the boys accept the invitation and board a steamboat for Arkansas.

Tom’s opportunities to shine as a detective begin right on the boat, when a cabin neighbor won’t leave his room for any reason. Curious, he and Huck disguise themselves as porters just so they can get a glimpse of him. In a coincidence that could only make sense in Twain’s Very Small Town U.S.A., Tom recognizes the room’s mysterious inhabitant as none other than Jubiter Dunlap. Surprised at being recognized as such, the stranger takes the boys into his confidence. He is not Jubiter but rather Jubiter’s identical twin Jake, and a burglar of the highest order. He and his partners stole some large diamonds in St. Louis, but he absconded with them and is now trying to disappear and then return to his brothers, whom he hasn’t spoken to in many years. He shows them the disguise he’s made to escape his ex-partners’ notice: a deaf, dumb bearded man with the diamonds cleverly hidden in the soles of his boots. Wowed by the romance of the situation, the boys offer to help him. They make plans to meet him the woods near his brother Brace’s home so they can inform him about any suspicious characters lurking around the town.

However when the boys approach the sycamore grove where they planned to meet Jake, things start to get real; they hear a number of cries for help; they see a man carrying something that looks large and heavy; they see a man in Jake’s disguise pass them but take no notice of them. Worried the thieves caught up with Jake and that what they saw was actually his ghost, the boys retreat home and wait to hear of a murder. What they do hear, however, is not what they are expecting: Jubiter Dunlap is missing, and Brace blames Tom’s poor distressed Uncle Silas.

What follows is the kind of identity tangle that Twain loves so well (a plot device he used most notably in The Prince and The Pauper, Puddin’head Wilson, and Huckleberry Finn). The ghostly man in Jake’s deaf and dumb get-up wanders the woods and won’t do anything but gurgle at the boys, and the buried body Tom and Huck find with assistance of a borrowed bloodhound is beyond recognition but is wearing Jubiter’s clothes. In the boys’ excitement over being a part of a real mystery (as opposed to the role playing they engage in back in Missouri), they run home with news of finding what they think is Jubiter. Their actions have disastrous consequences, however Silas admits he killed Jubiter and now that they’ve found the body he must turn himself in.

What follows is the kind of identity tangle that Twain loves so well (a plot device he used most notably in The Prince and The Pauper, Puddin’head Wilson, and Huckleberry Finn). The ghostly man in Jake’s deaf and dumb get-up wanders the woods and won’t do anything but gurgle at the boys, and the buried body Tom and Huck find with assistance of a borrowed bloodhound is beyond recognition but is wearing Jubiter’s clothes. In the boys’ excitement over being a part of a real mystery (as opposed to the role playing they engage in back in Missouri), they run home with news of finding what they think is Jubiter. Their actions have disastrous consequences, however Silas admits he killed Jubiter and now that they’ve found the body he must turn himself in.

The novel jumps fairly quickly from there to a courtroom scene fit for prime time. Eyewitnesses confirm the bad blood between Silas and the Dunlaps, testify to seeing a shadowy figure doing a shadowy thing on the date in question, and even claim they saw Silas commit the murder and bury the body. Silas himself confesses to the murder in a dramatic burst, and a soundtrack of gasping, muttering, and weeping backs the entirety of the proceedings. But through the hullabaloo, Tom, who is certain something is wrong with the picture, is paying Sherlockian attention to detail, looking for cracks in the testimonies, and searching the room for any scrap of evidence he is missing.

Finally he sees it: the deaf and dumb stranger, whom he and Huck thought at first was Jake’s ghost then a live Jake laying low, is present for the trial (unremarkable, since the whole town is present), and as things heat up the stranger is succumbing to a nervous tic that Tom had previously observed of Jubiter. Suddenly the truth of the situation comes to him, and he stops the trial in order to reveal a sinister plot of Brace and the very alive Jubiter to frame Uncle Silas for murder. The thieves did catch Jake and they beat him, but, startled by approaching men, they left before he was dead and they did not take the boots. Jake, beaten beyond recognition, seemed an opportunity to the Dunlap brothers, who had come to see what the commotion was. They killed and buried Jake and dressed him in Jubiter’s clothes, and then Brace snuck into the Phillips’ home, put on Silas’ work smock, and buried the body. In an attempt to hide in plain site, Jubiter put on the strangers’ disguise, diamond soled shoes and all. They paid witnesses to exaggerate their testimonies, and they allowed somnambulist Silas to believe that something he’d probably dreamt of doing many times was something he had actually done. The scheme was going so beautifully that Jubiter forgot himself and began to act like Jubiter in the courtroom. Needing more evidence to prove the man Jubiter and not Jake, Tom asks for the boots, which Jubiter yields willingly, having no idea that there are diamonds hidden in them. In addition to enjoying the glory of having solved the mystery and absolved Uncle Silas, Tom is granted the award for the jewels’ return, which he dutifully splits with Huck as a reward for Huck’s loyalty and assistance (the third such fortune the boys come into and split down the middle, the first two occurring in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and in Tom Sawyer Abroad).

Sprinkled throughout the novel, which is narrated by Huck, are digressions in praise of Tom’s intelligence. An example:

I never see such a head as that boy had. Why, I had eyes and I could see things, but they never meant nothing to me. But Tom Sawyer was different. When Tom Sawyer seen a thing it just got up on its hind legs and talked to him told him everything it knowed.

But Huck isn’t all praise. Observances of Tom’s arrogance pop up, too. After Tom allows a too pregnant pause to precede his explanation of the crime to his captive audience in the courtroom, Huck explains that “he just done it to get an ‘effect;’ you couldn’t ‘a’ pulled him off of that platform with a yoke of oxen,” and that “it was nuts for Tom Sawyer to be a public character thataway, and a hero, as he calls it.” These opinions of Huck’s aren’t new; Twain had established them right at the beginning, in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. But any Conan Doyle fan would notice that in the context of a mystery Huck becomes a perfect Watson to Tom’s Holmes, happy to act as the loyal inferior the Great Mind, to risk danger in order to observe the detective at work, and to record the events as honestly as possible.

Twain had already fallen in with the forensics trend the plot of 1894’s Puddin’head Wilson relies almost entirely on the value of fingerprints as conditional evidence. That he would apply his already celebrated and charismatic Tom and Huck to the genre makes sense, especially considering how many similarities their relationship already shared with Holmes and Watson. Ultimately, however, Twain was a humorist, and though he is able to use Tom and Huck to mimic Conan Doyle’s style (no small feat), he doesn’t match it. Not only is this mystery less than challenging Tom benefits from something Holmes rarely possesses in the same way, which is prior knowledge of a major piece of evidence in the case.

Twain had already fallen in with the forensics trend the plot of 1894’s Puddin’head Wilson relies almost entirely on the value of fingerprints as conditional evidence. That he would apply his already celebrated and charismatic Tom and Huck to the genre makes sense, especially considering how many similarities their relationship already shared with Holmes and Watson. Ultimately, however, Twain was a humorist, and though he is able to use Tom and Huck to mimic Conan Doyle’s style (no small feat), he doesn’t match it. Not only is this mystery less than challenging Tom benefits from something Holmes rarely possesses in the same way, which is prior knowledge of a major piece of evidence in the case.

Though Tom’s discovery of the diamonds involves disguise and intrigue, it isn’t disguise or intrigue employed in an effort to solve the murder mystery. Holmes does have a bank of knowledge about local characters and goings on that he occasionally draws from, but he ussually doesn’t have smoking-gun style information like the stolen diamonds in Jake’s boots. Part of Holmes’ charm is his ability to solve puzzles using clues that are visible to everyone but that everyone doesn’t notice, so this difference is significant. Also, Tom suffers from sentimentality about the people involved in the case that Holmes never really experiences; feeling that he has betrayed Silas by finding the body, Tom dedicates himself to the case with a new vigor, hoping not only to demonstrate his intellectual superiority but also to absolve his uncle of the crime, which would never be a motive for Holmes. But again, Tom and Huck are already established characters, and though they fit into the roles of Holmes and Watson, they can’t behave in exactly the same way.

In spite of it’s shortcomings as a genre piece, the novel features Tom and Huck at their charming, versatile best and is a clever response to Conan Doyle’s success that any fan of either writer should take a look at.

Allegra Frazier is a writer, editor, and visual artist living in New York. She founded the Brooklyn-based literary magazine Soon Quarterly, and her work can be seen in The Brooklyner, in The Short Fiction Collective, Storychord, and elsewhere.